The kingdom breaks in

Suzanne and I treated ourselves to a day at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. We spent the entire afternoon in the galleries, and hung around for Art After 5 and a jazz set by Orrin Evans to avoid the Friday afternoon traffic on the Schuylkill. It was a great day.

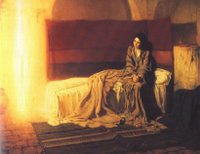

I almost skipped the American wing, but I'm glad I didn't. I'd forgotten that one of my favorite paintings, Henry Ossawa Tanner's "Annunciation," was there among the Eakins' and PA German furnishings. PMA has several paintings of this famous scene from scripture -- there's one of a thoroughly European Mary at her books at a green-clad table when she's surprised by Gabriel, and I recall one with Mary in regal blue robe and golden halo. Tanner's "Annunciation" stands out because it's so real yet so otherworldly.

Tanner, son of an African Methodist Episcopal bishop, painted his "Annunciation" in 1898. His Mary is an ordinary peasant girl, in everyday robes, in a thoroughly modest bedchamber. The painting is remarkable for its unremarkableness, given the subject matter. Often religious artists pay homage to the venerable Mary, with radiant countenance, a sublime expression, and of course the halo's glow of near-divinity. Tanner paints her, instead, as if she were you or me: Sitting up on the edge of the bed in surprise, studying the angel with a cross between serious inspection and incredulity. One isn't sure, from his rendition, if the teen is going to say "No way!" or "Whatever."

Against this background, Tanner's handling of Mary's otherworldly visitor is surprising. Rather than the familiar hyper-realistic, vaguely militaristic winged figure, he paints Gabriel as a sliver of intense, unrelenting light. His angel seems to be materializing, as if he had a premonition of Star Trek's transporter beams. Interstingly, the bright beam plays against the shelf on the wall to create the appearance of a cross. There's no other source of light visible in the image. Imagine how dark and cold Mary's room was before Gabriel appeared.

To me, Tanner has created more than a snapshot of a moment in the Nativity narrative. His "Annunciation" is an icon of how God's kingdom breaks in amid the ordinariness and grittiness of life -- not just to Mary, not just in Bible times, but still, today. The more formal, formulaic depictions are beautiful and meaningful, and speak important realities about the story. But Tanner's vision of the Light illuminating the bleak, plain and completely recognizable place where Mary sits, alone and puzzled like us, gives hope that the divine can touch even our cold, dark recesses. A God who breaks into this reality and transforms it, who can change the world through one timid, confused teenage girl -- now there is good news for all of us!

The theme of transformation was underscored by the exhibit that contrasted New York and Paris paintings by Beauford Delaney, another African-American artist born three years after Tanner painted his "Annunciation." Delaney honed his skills in portraiture and expressionist cityscapes in New York in the 1940s.

In 1953 -- at age 52 -- Delaney took a trip to Paris that was to have lasted a couple of months. He stayed there until his death in 1979. In Paris, he felt freed from the double prejudice he faced in America as a black, gay man, and his work immediately opened up. From his first days he experimented with color, abstraction and new forms.

I looked at a number of paintings in new ways today. The other Annunciation I mentioned, with Mary a literate school girl reading at her desk, shows that through history people have worked to contextualize the gospel story so that they could see themselves in it, and thus believe it and participate in it. And I marvelled at the very realistic master renditions of familiar scenes, such as the crucifixion. In one the detailed faces of the crowd were painted in different scales, and the annotation suggested that the artist had acceded to the wishes of some patrons to be made more prominent. What an act of faith it could be if we, like these patrons, could actually see ourselves in the gospel, both worshipping Christ and participating in his execution. Maybe it could be an act of devotion to Photoshop(R) our images onto these masterpieces to locate ourselves, as well, in the midst of the story?

Comments